by Peter Donovan

|

Peter Donovan photos

Wildwood Forest

|

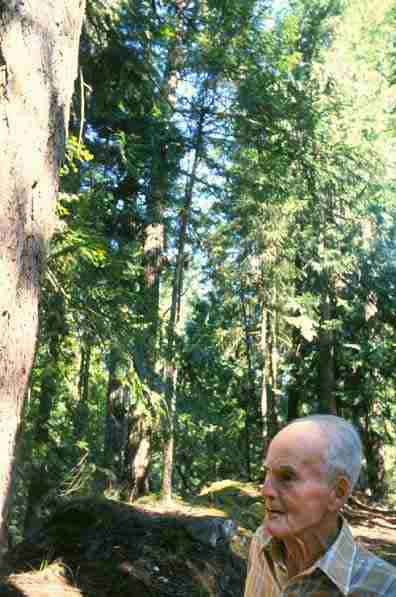

On 137 acres near the east shore of Vancouver Island, Merve Wilkinson has spent a lifetime learning about managing for a whole forest. His example has enlarged people’s view of what is possible with forest management in British Columbia and elsewhere. Thousands of people visit Wildwood each year, including foresters from all over the world. Merve continues to enjoy learning and teaching.

Merve bought the property in 1938, which contained 1.5 million board feet of Douglas fir, grand fir, and red cedar. Times were tough, but the forestry he saw around him did not inspire him. Hoping to raise livestock or poultry, he enrolled in an agriculture course at the University of British Columbia. There he met a Danish professor, Paul Boving, who was familiar with Scandinavian forestry ideas and encouraged him to do forestry, and to keep learning after graduation.

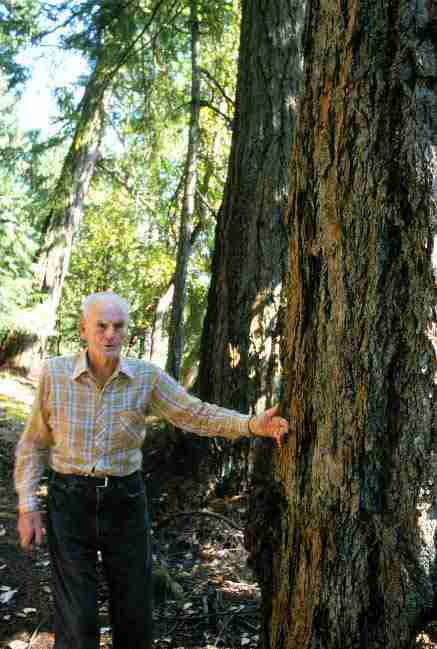

In the 1930s, Merve says, there was lots of knowledge about trees but little about forests. To this learning task, Merve has brought an open and independent mind, practical skills and experience, a disposition to work with nature rather than against her, and observation. In his mid-eighties now, he still fells his own trees.

Merve began logging his property in 1945, cutting selectively. Since then he has logged 2.1 million board feet. There are lots of stumps, but there are also plenty of big trees. A 1996 timber cruise estimated the standing volume at 1.65 million board feet, 10 percent more than in 1938.

He manages for a multiage, multiheight, multispecies forest—in sharp contrast to the even-age, industrial model that has prevailed in British Columbia, against which Merve is outspoken. “Rows of trees are not forests. They represent blind stupidity and a one-track mind.”

“Who makes the major decisions in our society? Experts! If a chairman of a meeting introduces me as an expert, I ask him to please correct it. I am a knowledgeable man. But expert is the last word I want connected with my name.”

|

“The forester has a legitimate role when he’s working with nature. He’s an illegitimate bum when he’s trying to kill nature. We’ve got too much of that.”

Merve compares raising trees to garnering interest on a bank account without touching the principal, which is the biomass of roots, trunks, canopy, and soil, with the myriad forms of life that make up the whole forest. “Harvesting of the trees can be done in cycles or continuously as long as the proper percentage is taken.” He now leaves 8 to 10 percent of his cut as coarse woody debris on the forest floor.

“A forest which is utilized economically cannot be sustained without being selective,” he says. “The two are interdependent.”

He harvests and thins to enhance diversity plus timber production. “When needle growth is down to 60 percent, you can seriously consider taking it out.” Merve keeps dead snags for wildlife such as pileated woodpeckers and numerous other birds who contribute to the stability of the forest by harvesting insects. He does not consider disease a problem at Wildwood.

Merve manages for a slightly more open forest than would occur without active management, and regeneration is natural. The Wilkinsons graze a small bunch of sheep over much of the property, which helps keep the underbrush back.

Wildwood has been a business and a partial livelihood for Merve, and furnished him with “a real good living style.” He has also done stonemasonry and built log houses, including his own which is entirely from his property with the exception of the carved pine door.

In 1990, Merve formed a partnership with sawmillers Mark Randon and Tammy Hodgeon. With a portable bandsaw mill, Mark and Tammy mill and market all of Wildwood’s lumber, some of which goes for specialty uses such as ship timbers and musical instruments.

|

Through Randon and Hodgeon, Wilkinson gets a premium price for his logs, as many customers know his management, have visited his tree farm, and can get the product and quality they want. In some cases buyers select trees. Third-party certification and labeling, a strategy designed to reward good forest stewardship via a higher price for labeled lumber, has not been needed, though Merve regards it as a good step for the industry.

“When Mark got his mill,” says Merve, “he put one ad in the paper. It just took off. The shipwright got into the game because Mark cuts his wood the way he wants it. He repairs wooden ships all over the west coast.”

Merve’s logs, which are sorted, bucked to length, and sawn according to customer preference, keep 26 people occupied. Some of them are hobbyists, such as a mandolin maker who uses some of Merve’s Douglas fir. Processing and marketing Wildwood’s logs provides most of Randon and Hodgeon’s income. Merve doesn’t have to accept the prevailing rate at the major mills, and is able to participate in the entire cycle from production of wood fiber to end use. Quality, sustainability, good economics, and customer satisfaction are the outcome.

Merve deplores clearcutting, which effectively reduces the production of marketable timber volume per acre per year to zero, and takes land out of production, sometimes for the long term. The social and economic impacts include thousands of jobs lost and devastation of timber towns.

In 1993, the MacMillan Bloedel company, a major licensee operating on crown land, refused to abandon its plans to clearcut a significant portion of Clayoquot Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island.

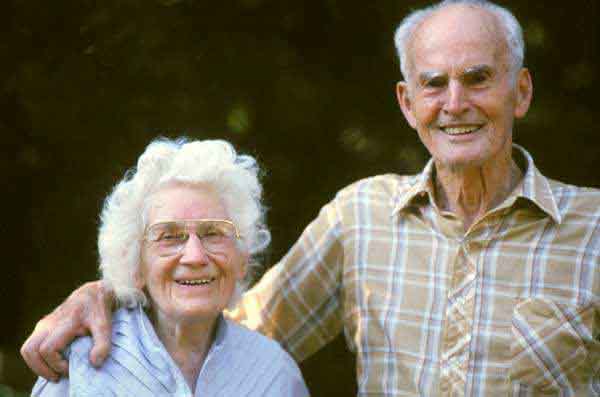

In August 1993, Merve and his wife Anne took part in a protest blockade of the access road. Merve convinced many of the demonstrators to protest clearcutting rather than timber harvest per se. Merve and Anne were arrested (along with 850 others) for ignoring the British Columbia Supreme Court injunction against interference with MacMillan Bloedel’s plans. During the trial, Merve told the judge, “My Lord, it is not necessary to destroy the forest to extract timber. It is a matter of method.”

Merve and Anne Wilkinson

|

Merve was sentenced to 100 hours of community service, which he was not allowed to do in forestry. He says the Clayoquot blockade worked, to an extent. “It alerted a lot of people to what’s going on.”

“We need more people and fewer companies involved in the forestry process—community participation along with environmental people and practical logging personnel. Contrary to many opinions we have people who would and could do what is needed.”

However, resistance to change is widespread. Wilkinson once heard a MacMillan Bloedel forester explain, “the reason we won’t do alternative forestry here is that we would be admitting that we know how.”

“They won’t do it until they have to,” says Merve. Three things are required for change, he says: good forestry education, laws, and public awareness.

Ruth Loomis, coauthor with Merve of Wildwood: A Forest for the Future, observes that “the essential ingredient in effective woodlot management is time—a long-term perspective and a day-to-day participation in a living landscape that evolves over decades and even centuries.”

First published in Patterns of Choice: A journal of people, land, and money, 1999.