by Peter Donovan

VERNON, BRITISH COLUMBIA--For decades, large timber corporations have been calling the shots in the management of the province's seemingly unlimited forests. As the end comes into sight, conflict has escalated over the biological, social, and economic consequences of converting huge acreages and volumes of timber into cheap dimensional lumber and pulp for export.

In an innovative experiment begun in 1993, the Vernon district of the B.C. Ministry of Forests created an open-market log sort yard as part of their Small Business Forest Enterprise Program. Though the volume is relatively small, the results so far include a full spectrum of environmental, social, and economic benefits, without undesirable side effects. These results include value-added businesses, more and better jobs in the woods, more environmentally sensitive forestry, and a better bottom line.

Less than 10 percent of the province's land area is privately owned. The Ministry of Forests (B.C. Forest Service) manages the forests on crown land. In the 1940s the province set up the tenure system, where timber companies had a guaranteed volume in order to stimulate economic development. The inspiration for this was the Shelton Sustained Yield Unit in Washington's Olympic Peninsula, where the U.S. Forest Service formed a special relationship with Simpson Timber, which built mills, roads, and provided jobs.

Says log sort yard manager Tom Milne, "thirty years ago there were small mills behind every tree. It turned the corner in the 1960s. People who were active in utilizing a certain volume of timber received a quota to that amount. Many of these people were small operators. Many of them sold their quotas to the larger quota holders."

Through the 1970s and '80s, small independent loggers and sawmills were disappearing. Says forester Jim Smith, "almost all the wood in B.C. is tied up by the big companies, and if you want to buy a log in this province you're out of luck."

The Ministry of Forests sells most of its timber at a set price per unit of volume. The "log it or lose it" tenure system provides few incentives for stewardship-oriented forestry. The provincial Forest Resources Commission (FRC), which included citizens and a politician or two, published a study in 1992 that concluded

The Commission believes that the establishment of a province-wide log market represents the only way that the province can realize full value for its resources and generate the income required to fulfill the enhanced stewardship role of the Vision Statement. The measures foreseen by the FRC in establishing a market are neither cumbersome nor costly to implement. The basic requirements are simple: a sufficient volume of logs available for interested purchasers; a notification system that lists (by location) the present and future availability of logs by size, species, and where possible grade; and a reporting of transaction prices on a similar basis. Given open access by sufficient buyers and sellers, the market will make itself.Jim Smith was the Small Business Forester for the Vernon district, in the Okanagan Valley. A core team of people in the district office were committed to seeing the forest resource as more than just timber, including timber technician Tom Milne. The FRC report came along at the right time, and Milne and Smith proposed to their superiors the concept of selling logs rather than standing timber--a considerable departure from the usual practice of turning over volume quotas at a set price. They felt that the FRC recommendation would be good for the province, and could lead to long-overdue reform of the tenure system, making wood available to anyone.

"Because we do not have a truly competitive log market," says Smith, "the provincial government (and thus, society) captures only a fraction of the value of timber that is cut. We wanted to test the concept of an open log market for some of the 160,000 cubic meters we cut annually through the Small Business program."

In March, 1993, says Smith, "they gave us the go-ahead--$2.2 million, make it work. We had to scramble like mad. There was no real idea of how to put this sort of thing together. We had to come up with a policy, procedures, forms, all kinds of things. It received strong support from the Forest Service executive, and we made it happen. Tom Milne came on as manager in May. The first load of logs came into the yard in August and Tom hasn't slowed down since."

"Tom is a good manager. He has a heart for the common man, he understands the industry extremely well, and he has an open mind. He's not afraid of change, he's willing to try things, and make adjustments. He's willing to deal with changing conditions and try to make them work. There have been other log yards started by the B.C. Forest Service, and they've gone down because they haven't had that entrepreneurial spirit, that confidence or the ability to change as the market changes."

Milne had experience as a woods manager, including a stint running a log yard for a sawmill. "He pretty much knew what had to be done," says Smith. "My approach to much gentler forest management fit right in with the Forest Service goal of testing partial-cutting silviculture systems. That was fairly easy to do. For Tom to get the log yard up and going was much more difficult, in that there were no models to work from."

Milne says, "it is a privilege to be able to go and take all my ideas, particularly working in government, where there's a million policies and regulations. I've been somewhat given free rein to practice some different things. Stay within the law, wobble around the policy a little bit. Freedom to manage, allowance to take a few risks. Good risk management practice is what this has been all along. See what people want, test your theories. I'm always thankful to the Ministry for backing me in this opportunity."

It was high-visibility project. "People never forget a failure. They forget successes." Even though relatively small volumes of timber were involved, resistance was likely simply because the project represented change, and implied criticism of the current system.

How the market works

The first location for the Ministry's log yard was a leased 30-acre industrial site near Lumby. In 1996 the log yard moved to a better lease arrangement outside Vernon.

The logs come mostly from Forest Service Small Business timber sales on the Vernon district. The log yard's loaders unload the trucks and spread the logs on the ground with the butts all one way, tops the other. The contract log scalers hired by the Ministry scale (measure) each log, and paint-code each log according to sorts based on species, grade, and likely use. The log yard started with 11 different sorts, and is now up to 48 five years later because of market demand. After scaling, and some bucking to capture the highest value, each sort is piled separately. When a given pile of logs reaches a marketable quantity--which varies for each sort--it is ribboned off and sold by sealed-bid auction. Thus the buyers set the price, in sharp contrast to the way most timber changes hands in the province.

The log yard started with 11 different sorts, and is now up to 48 five years later because of market demand. After scaling, and some bucking to capture the highest value, each sort is piled separately. When a given pile of logs reaches a marketable quantity--which varies for each sort--it is ribboned off and sold by sealed-bid auction. Thus the buyers set the price, in sharp contrast to the way most timber changes hands in the province.

Bid sales occur every week, and are advertised in newspapers. Some bidders regularly come 300 miles, and most inspect the logs before bidding. The high bidder has five days to pay and seven days to remove the logs. The log yard loads them onto the buyer's designated trucks. The sort yard sells about 55,000 cubic meters each year (about 1.1 million board feet, or about 5 percent of the annual volume coming off the Vernon district).

Says Smith, "there's wood available to anyone, and you end up with all kinds of synergies happening. You get all kinds of ideas." At the log yard's office trailer, the coffee pot is always on. There is a steady stream of visitors. Milne is a committed marketer and educator, and the crew at the log yard has nicknamed him Coach.

"It started off going in the right direction," says loader operator Steve Bernhart. "We've shown the way. Everybody that comes in is looking for something different. Tom goes out of his way. If they're looking for something, we'll set it up, and if it works, we'll do it. If not, we tried it, we'll let it go."

Says Milne, "I always ask, what brought you here? They say, 'we come here and we don't feel intimidated.'"

The log sort yard will sell single logs or even parts of logs. Once a high-school student bought two eight-foot log sections for a school project, and took them to a small sawmill in his pickup. "He was going to make something out of it. Some kid's going to come up with a hell of an idea. Plus they get that feel of what a log is."

Though the open-market log sales return a handsome profit to the Ministry, "the buck isn't the big thing," says Milne. "It really becomes an important part of a community. A lot of guys come to our sort yard just for coffee and to see what the price of wood is. Many people are just interested, naturalist club. A grade 11 class comes from the Yukon every year."

"We talk about logging, bugkilled wood. Some people have never heard that before. At the sort yard I can take the time to do that, because I don't have to put 50,000 board feet in a mill and yell at people. Pretty soon, logging's not bad, they understand beetles, they understand the logger, they start looking around at their forest, it starts to mean something."

The interest results from the way the logs are sorted, the open market, and the "mindset change" as Milne calls it, where people can begin to see a log as something other than pulp, veneer for plywood, or 2 by 4s. "There's nothing magical about the wood we have here that's different. It's just knowing your markets, and what people want."

"We watch. When we get bins of a certain size, we sell them. Quite often, somebody is looking for that type of wood, but for something entirely different. If you shut her off at 3 or 4 loads, they tend to want to buy it. If you had 25, they can't afford it. Those are the little tricks I use to kind of smell out what's going on."

The customers

"One guy, he was looking for a beam, 10 by 24 inch, 40 feet long. That's a 27-inch top, that's a fairly big tree. I said the only ones I have are in my character wood. They have knots, they're kind of ugly. You can't ship them to a mill, because they can't handle them. He came in and picked one out. He paid $350 for that log. He just couldn't get it anywhere."

The "character wood" pile consists of logs that are defective for most conventional uses because of knots, twists, forks, or curvature (called "sweep"). Log-home builders buy some for decorative posts, beams, or distinctive stairways. Milne sells others as large woody debris to place in streams to enhance fish habitat. "That cedar over here, that basically is all reject, cull, junk. The guy that was cleaning up the yard asked us if we wanted to put it in a pile and bury it. I said no no, I'm going to sell it. A week ago, an old guy came in, bought the whole thing for $40 a meter. You're talking $1200 in lieu of burying it. He wants it to make fence railings and flower pots. But he couldn't buy it anywhere else at that price and volume."

"That cedar over here, that basically is all reject, cull, junk. The guy that was cleaning up the yard asked us if we wanted to put it in a pile and bury it. I said no no, I'm going to sell it. A week ago, an old guy came in, bought the whole thing for $40 a meter. You're talking $1200 in lieu of burying it. He wants it to make fence railings and flower pots. But he couldn't buy it anywhere else at that price and volume."

"We're selling firewood for $400 a truckload. There's lots of people who want it now. They're afraid to go cut in the bush because of private property or wildlife trees. We sold 15 truckloads last year. It's a way of dealing with your waste." A pulp company pays the log yard $75 per bin for junk wood that is not salable otherwise. Says Milne, "that's how you can turn things around."

Most sawmills prefer green wood. Dry wood that comes from salvage logging makes up several sorts at the yard. Milne says, "We have people from 150 miles away who are getting into this stuff for beams and different things because they are already dry and they don't have the kiln facility. The drys are actually getting to be quite a market, but nobody sorts them."

Dry logs are sought by log home builders, saddletree makers, and manufacturers of chopsticks, pine shakes, musical instruments, windows, and doors. Instead of selling them as low-grade sawlogs at $50 or $55 per cubic meter, Milne has averaged $90 for the dry sorts.

|

| This tree with a triple trunk would have been cut up, but it is destined for the sort yard, where it's unique form may attract a buyer. |

"One guy, he showed me a picture, he's building real beautiful outhouses. He comes with his wife and a horse trailer, and he picks out what he wants, we scale it up, and away he goes. He's got contracts with the parks and resorts to build these natural-wood outhouses."

Though regulations at first required Ministry of Forests timber to be sold on a bid basis, Milne eventually got permission to sell direct, without a competitive bid. The price is based on last week's bid price for that particular sort.

"This guy phoned me up, he said I'm making pallets. I need pine. I said, do you need dry or green? Well, I need green, I need about 6-7 inch top. Well, that pretty well fits our pine peeler sort. Oh, he said, I'd like about 3 loads a week. He said, I don't have time to go out into the bush, I really don't know a lot about the bush. But he really knows how to run his mill and make pallets. We now supply him with logs at competitive prices."

"They're just little spinoffs, but there's probably 15 or 20 of them," Milne says. "They're small, but they keep families going. All this other wood is not what they want. The major mills want that type of wood. There is really not the conflict for the wood that people fear."

"It's like the Field of Dreams," adds Milne. "You build it and they will come. People dropped in, saying, 'I need this kind of material.'We sorted for it. When you gave them what they wanted, a going rate wasn't the problem. These sorts didn't hurt anybody else."

Doug Rouck, with his brother Earl, runs a small sawmill east of Lumby. Around 1981 they began to move toward more value-added and specialized wood products, such as log home kits, cedar products, and flooring. "The idea was to chase the wood around the mill and get more out of it, instead of trying to cut more," says Doug. There were plenty of mills that were pumping out 2 by 4s and 2 by 6s, but people cover these with sheetrock and siding. "We want the stuff that goes on the outside and the inside, that looks nice, that's what we want. What people see."

Comments Tom, "there wasn't more wood available. The one thing you always heard, was 'How can we get more volume?'I thought, there's lots of volume there, but it's going to the wrong places. There's a hell of a lot of house logs out there, but you just have to quit making 2 by 4s out of them. There's a hell of a lot of wood that Roucks are expanding on, let's not butcher it into chips, let's sort it. If you want to make 2 by 4s out of the building logs, it's $150 a meter. If you want to use a sawlog, that's only $76."

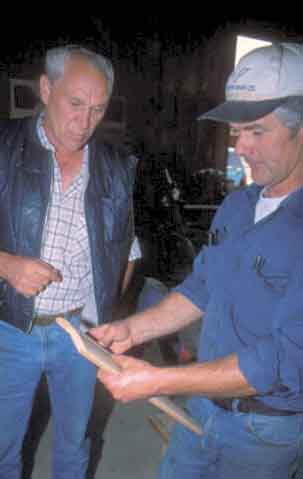

|

| Tom Milne and Doug Rouck look at flooring. |

"It proved out in the price sheets over five years. If you sort the wood to what that guy wants, nobody's going to beat him on the price. The little guy can pay as much, he just doesn't want to buy a whole bunch of extra crap he's going to have to peddle, burn, or lose. You give him what he wants, he'll pay his way and then some. Doug's a classic example on cedar poles. Nobody could touch him. Nobody was coaxing him, he was just bidding to where he could make money."

Says Rouck, "we used them for log homes, or we resawed them into siding or other board products. You've got real nice wood, no defect, she's straight. You know what you're getting."

Milne says, "There's a case where pole companies were $25 a meter short [on their bid]. That whole mindset of the little guy can't pay his way, that's proved wrong time and time again."

For Doug Rouck, the log yard "is an advantage, for sure. It gives me a crack at buying the high-grade stuff. Peelers for example. I can go there and buy straight peelers. It's what I need, what I want. We can kind of plan our year around the sort yard because of the sales coming up. It's easier than me running all over the place looking for wood."

Sawlogs, normally processed into dimensional lumber, are selling for about $60 per cubic meter at the log yard. Fir peelers, normally processed into plywood veneer, are selling in the $100 range.

Says Milne, "our volume is not a big deal, only .07 percent of the total [in the province]. It satisfies a lot of needs. It doesn't supply all of Doug's or anybody else's, but it takes the heat right off."

"Everything's swung butt one way, top the next. He looks at it, he sees his short/long component, he can see exactly what he's buying, the rots, the average diameters. It's far easier to do it this way than buy bush-run material."

Adds logger Brian Kowalski, "it's ready to throw on the chain into the mill. Sorted, scaled, bucked, and graded."

Logging

Though about 85 percent of British Columbia's crown timber is controlled by mostly corporate licensees, about 13 percent is auctioned as standing timber, much like U.S. Forest Service timber sales. The Small Business Forest Enterprise Program auctions standing timber to small logging companies and contractors. In 1993, due to a tenure transfer, the volume assigned to small businesses operating in the Vernon district increased to 160,000 cubic meters.

Jim Smith led the planning effort. "Translating a holistic vision into reality begins with a good plan. We didn't look at nontimber values as problems, but rather as opportunities to demonstrate appropriate forestry. And we had fun doing it! We had forestry contractors develop Total Resource Plans for the 84,000 acres in our operating area. As often as possible, we established silvicultural systems that protected or enhanced the values in the forest. We established a policy of taking the worst and leaving the best, and applied these methods to 65 percent of the area we planned for harvest."

About a third of the Small Business volume went to the log yard, which "worked extremely well with the small business program," says Smith. "We could schedule our timber sales--they became harvesting contracts--and we would have control over when they were going to be logged, and we would have much more control over the logging because the logging contractors were working for us. That was a bit controversial, but it worked extremely well. The loggers really liked it, because they weren't taking any market risk. They were being paid a fair price to log and haul the wood. They knew they were going to get their money, they knew they were going to get fair scale, and that's quite an issue up here. Even though British Columbia is fairly redneck and right-wing, in this industry, running a government log yard fit in extremely well with the small business program."

Another advantage, says Smith, is that the logging happens relatively quickly, and the government gets its money 3 or 4 weeks after the logs go into the yard.

The contract loggers who work for and are backed by the big companies generally aren't interested in a harvest and haul contract because they don't get the timber. Says Tom, "So all those little guys that are good loggers also, they now have more of an opportunity to bid on a logging job. They have a skidder, and a little Cat, a pickup. Basically all my loggers are small independent loggers. His competition is those of his own kind--the small, entrepreneurial, independent logger, who likes to log because of a way of life. He doesn't want to broker wood, he doesn't want to sell logs, he wants to go log it."

Resistance

The success of the Vernon log yard and small business program has raised the question, have we been doing it wrong all these years? This question applies in government as well as industry. When Tom Milne can generate wealth by sorting logs and selling in an open market, this can and will be perceived as a threat or indictment. He has had his share of political difficulties, including a move by the government last winter to close the sort yard.

Says Brian Kowalski, "They [major licensees] still have the idea that they own it all, and we're trespassing and stealing wood off them. We didn't know what to think when it first started. A log buyer [for one of the major companies] told us, 'we can do better for you guys.'Anything government-run is a screwup. The only reason it worked is Tom."

Says Tom Milne of the loggers, "we've never allowed them vision, passion, responsibility. You give them some good direction, they'll give you an excellent job."

Now, says Milne, more of the major companies are realizing that there are some economic possibilities in the open market, with sorting, and they come to the log yard to buy exactly what they need. Eight major sawmills and pulp manufacturers are a crucial element of success, as they buy 75 percent of the log sort yard's volume. "This year a lot of the major companies were quite concerned that we might not be running. Yet five years ago, they were skeptical of our intent. It became an asset to them, another place to come."

"Some of these wood buyers, they've been around a long time. I come right out and ask them, what do you think of the sort yard, Steve? And he says, 'well, I'll tell you, I like it. Because I have an opportunity to buy wood here that I would never get an opportunity to buy. Because it comes here, I get a crack at it. It just gives me that much more.'Every Thursday he's in here for his cup of coffee, puts in his bids."

"What I hear is, 'We're probably going to buy more wood from the sort yard than from the loggers in the woods, because we can see what we're buying, it's already scaled, there's no liens on it, and the stumpage has been paid.' Just the opposite thinking from five years ago."

Resistance came from the government side as well. Jim Smith says, "even though Tom didn't have the authorization to sell wood direct, he did it anyway, and I backed him on it because it was the right thing to do. We weren't supposed to restrict timber sales to Category 2 (which is small sawmillers). But we did anyway because we thought it was the right thing to do. We got into trouble. We operated on the philosophy that it's easier to get forgiveness than it is to get permission. And lo and behold, after a couple of years, the Forest Service changed their policy. They said that we could sell direct, we could restrict tenders to certain categories."

"The government would be very hard-pressed to shut it down. It has become so popular, amongst so many people. The environmental community really supports it--big-time outfits like Greenpeace and the Sierra Legal Defense Fund really like it."

In 1995 Greenpeace took part in an experiment that certified logs from one Small Business sale as sustainably grown, and sold them through the yard. Because such certification implies that other logs are not sustainably grown, the reaction from the industry side was extremely negative, and Smith and Milne nearly lost their jobs. Nor was there a developed market for certified logs. Milne believes certification "will build itself. It's about sustainable forestry, and a higher value for logs once the market demand builds."

Benefits

Scaling, handling, sorting, and selling logs is an expensive proposition. The log yard charges $12.50 per cubic meter for selling logs that do not come in under the Small Business program. Some private operations boost their profits by selling their logs through the sort yard.

In spite of the costs, the sort yard returns one and a half times the cost of its operation to the Ministry in the form of increased revenues from the sale of logs. The key to this is the fact that the buyers set the prices on a bid basis, and there are a sufficient number of interested buyers who make regular visits to the centrally located log yard.

However, because of government accounting procedures, the profitability or wealth generation is hidden. Says Smith, "the Treasury Board has got to put out about $2 million a year, and they get back 5 or $6 million, but the budget boys only see this money going out. One of the excuses the Forest Service uses for not expanding the program is that the Treasury Board says they don't want to put out this extra money. If you look at the whole picture of course, financially it's extremely lucrative." But the log sort yard does not have access to the revenue it generates, and must depend for its operation on a budget allocation.

This year log prices are down. Tom says, "we're going to make all our money, pay all our bills, in the worst market time probably we're going to experience for a long time, but we're still going to generate revenue on the people side [employment and profit]. That's my forecast. That's better than the average."

By increasing the income from the sale of logs, over and above the extra handling costs, the Forest Service can justify smaller-volume, more stewardship-oriented forestry that employs many more people per unit of timber volume than massive clearcutting does.

In past years the log yard has generated 30 or more direct jobs logging or working in the sort yard. Log truckers delivering to the yard in the afternoon can often get a backhaul, hauling wood for a buyer. The yard has also stimulated value-added wood-manufacturing businesses. The saddletree maker, says Milne, bought $700 worth of wood from the yard last year and used it to make $60,000 worth of saddle trees. "That's value-added. That supports families, the community." He adds, "The sort yard is not the total answer, but it's a piece of the puzzle."

|

| Tom Milne. The saddle tree behind him was made from one of the log yard's dry fir sorts. |

What they learned

Steve Bernhart: I've learned a lot about why things are the way they are. I've learned a lot about the structure of government, the forestry.

Jim Smith: I know that we can do a very gentle job of forest management and respect all the values of the forest, the water, the wildlife, the views, the recreation. I know we can do it, and that it's economical and highly profitable. I have a lot of confidence in proceeding with that more ecologically oriented land-management philosophy, knowing that it pays. It doesn't pay as much as being thermonuclear, in the short run, but it is very profitable.

A big advantage to the Forest Service is that it's gaining hands-on experience in the industry in an entirely different way than it normally would. It's running its own logging operation. We have hands-on, real-life experience with the costs. The industry has always played those cards very close to its chest. So we know exactly what the planning costs, what the layout costs, what the logging costs, hauling costs, what it costs to run the log yard, what the competitive rates are on the logs, and we know that it's highly profitable to do a very gentle job of forestry. The industry's been telling us for years and years that it's not possible, it's too expensive, just wouldn't work. This program for the past six years has been proving beyond a shadow of a doubt that you can have an entirely different philosophy and approach to the forest and still make a big profit, and make wood available to a lot of people.

Tom Milne: What I've learned is that a lot of the mindsets we have: this guy won't do this, this guy won't do that, that'll never work--they're wrong. We've got to stand up and challenge them. All the stuff that we hear, and are led to believe--it's not all true. We've never made an effort to find out if it is. We've never explored what people's thoughts were on this type of concept, or what helps make things work in the real world.

People are receptive, responsive. It takes time for them to come, but they do come.

I always complain to the office manager and the district manager, jeez you guys, why don't you come out and see me? I would really like you to come on out to the yard, have a coffee. You know what their answer is? 'We got so many issues that we're having nothing but trouble with, we don't have any trouble with your sort yard, so we have to let you do that, we have to put our efforts in this.'

Maybe we're having problems in other areas because they never came and looked at the things that worked, and why. If it's a passion and a skill and a gift, then maybe we ought to start putting that in other things.

The forests should always be managed on the best interests of the communities--the economic benefits and the social aspects. In Cherryville, salvage logging and selective logging is a way of life for these people, they're proud of it. Don't take it away from them. You send them out clearcutting, they don't like it.

The problems that we inherited through environmental issues, it was never the logger's fault. Nobody can prove that to me. The logger is the guy who was hired to fall the timber, and if he didn't do it the way he was told, he was fired. It was us as managers of the forest who allowed it to go on.

If we got the bureaucracy and the politics out of it, turned it over to good forest managers and managed it for those three values [ecologic, social, economic], we would be making great strides, and we'd be healthy.