Paradigms and decision-making frameworks

by Peter Donovan (1997)

When we are dealing with paradigms and beliefs, there is no opportunity to choose without awareness. The following is an attempt at revealing what is usually hidden.

Some people may find it more useful to learn from specific situations in which people are applying these concepts. There are numerous specific examples in the topic areas at left.

For short descriptions of the nuts and bolts of holistic management, see also the Allan Savory Center for Holistic Management's website as well as other locations in our paradigms section.

This material is gathered from a variety of sources, including Allan Savory, Bob Chadwick, W. Edwards Deming, Jeff Goebel, Kirk Gadzia, and Roland Kroos. It can be copied, but please acknowledge sources and please copy with purpose.

What limits change in human affairs? What makes real change possible?

Paradigms are habits of thought, unstated rules, assumptions, or beliefs that define the boundaries we operate in. We are not usually directly aware of these habits of thought, nor are most of us taught about them in school or on the job. Much of what we "see" is determined by the reality behind our eyes--the "landscape of the mind."

Once a boy and his father were driving, and they had a bad accident. The father was killed and his son seriously injured.

At the hospital, the surgeon who examined the boy said, "I cannot perform this operation. This boy is my son."

How can this be?

Paradigms often limit our perceptions and awareness. We are unable to see something that does not conform to our basic assumptions. (We may assume all surgeons are men.)

The Greek thinker Aristotle represented the trajectory of a projectile as below, with forced motion on the left and natural motion to the right.  We who recognize Galileo's discoveries (many of which were paradigm shifts) "know" that the trajectory of a projectile follows an approximate parabola.

We who recognize Galileo's discoveries (many of which were paradigm shifts) "know" that the trajectory of a projectile follows an approximate parabola.

We can laugh at Aristotle. Yet Aristotle grew up in a culture where spears, rocks, and arrows were commonplace. In many cases he was a keen observer. Yet his concepts and assumptions--the truth of which we recognize--determined what he saw.

As it is said a fish is the last creature to discover the existence of water, we are often the last to see our own habits of thought.

In his book Discovering the Future: The Business of Paradigms, Joel Barker identifies five things about paradigms:

Paradigms are common, they are all around us and we all have them.

Paradigms are useful. They show what is important and help keep us safe.

People who create new paradigms are almost always outsiders.

People who switch paradigms have to have courage, because the documentation or evidence is not there.

Everyone can choose to change their paradigms (the choice is yours).

These last two have a great deal to do with leadership. It is said that management operates within paradigms, but moving from one paradigm to another requires leadership.

What today is impossible to do or change, but if it could be done, would fundamentally change your personal life, business, organization, or community from this point forward? Ask this question often. The answers will lead you to the edges where new paradigms are waiting to happen.

To shift paradigms, you must be willing to go back to the starting point. Albert Einstein observed that the kind of thinking that got us into the present situation is not the kind of thinking that will get us out of it.

How does human thought, and the paradigms that govern it, have the greatest impact on the world we live in? What type of human thought has the greatest and most powerful effect on our environment, our society and communities, our finances, and everything else?

Decision-making processes or frameworks

People use thought processes all the time to make decisions and solve problems. It is important to realize that everyone has some decision-making process, framework, or referent, even if it is unconscious, habitual, or unexamined. Paradigms or habits of thought have a great deal to do with the way we make decisions.

A wide-angle view of decision processes is outside the curriculum of most educational institutions or business schools. These kinds of things have only recently come into awareness. Even the concept of management, as a subject for study, is only about 50 years old.

The world in which our children and their children will live is built, minute by minute, through the choices we endorse . . . . These small choices, these trivial decisions, have as much weight in the long run as all of Napoleon's wars.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, The Evolving Self: A Psychology for the Third Millennium How would you characterize the decision processes by which we manage resources today? How about in the social sector--relationships, social services, etc.? How about in the financial sector--how do we decide what to do?

Here is a representation of popular decision-making framework.

Linear, reductionist, mechanical, reactionary, or universal decision-making framework

CONTEXT or SITUATION A problem, issue, or a symptom at the crisis point where the buck stops. Often the focus is on worst possibilities only.

DRIVING FORCE or GOAL Production, preservation, eradication/reduction, problem-solving

Examples: to reduce unemployment, to produce a full documentation package on the software, to eliminate wild oats from the fields, to preserve a natural area, to wean 600-pound calves, to harvest $450,000 worth of timber from the North Fork, to figure out what to do about your boss, husband, girlfriend, mother; to farm without using pesticides.

RESOURCES Money/labor, a budget or appropriation, equipment, facilities, water, wildlife, scenery, timber, minerals, employees, livestock, inventory, real estate

ACTIONS (TOOLS) Technology in all its forms (except in wilderness areas), Rest, and Fire

BASIS FOR ACTIONS Peer pressure, single criteria, expert opinion, availability of funding, research findings, past experience, cost effectiveness, cash flow, laws and regulations, how quick, compromise, or what is customary

FEEDBACK Did we solve the problem, or at least treat the symptoms? We often assume correct decisions have been made, and monitor to record results. In cases where we fail to solve the problem, we often tend to fix blame or pass the buck. Unintended consequences (such as environmental damage, social backlash and resistance, and externalized costs) typically become new problems, often for someone else.

Because this framework is problem-based, there are as many versions of this decision-making model or framework as there are problems, issues, or symptoms. New problems and subproblems are constantly being generated--as unintended consequences of dealing with previous problems or symptoms. Because of this, what we learn in one area of activity or investigation often is not able to benefit us in other areas. This decision-making framework limits knowledge and awareness, and under it many forms of knowledge (for example, local herbal knowledge) are certain to be endangered.

What we are here calling the linear or conventional framework is closely tied to the "expert model"--whereby decisions are referred to specialists.

A holistic decision-making framework

WHOLE UNDER MANAGEMENT We are in a situation of overlapping wholes. A management whole consists, at minimum, of people with their values, money, and resource base or land.

DRIVING FORCE: THE HOLISTIC GOAL The values the people in the "management whole" want to sustain; their best possible outcomes: quality of life, ways of producing this quality of life, and future resource base needed to sustain this production indefinitely

Examples: to achieve self-fulfillment through meaningful work, develop the skills needed, and the customer base and community to support this meaningful work; to live in harmony with the ecosystem while producing nutritious, quality food for caring and knowledgeable customers.

BASIC ECOSYSTEM PROCESSES Nature is process, not just a reserve or area. We depend on: The water cycle Energy flow Mineral cycle Community dynamics

ACTIONS (TOOLS) Technology in all its forms Rest Fire Living organisms (including grazing animals)

BASIS FOR ACTIONS In addition to the usual criteria, seven commonsense questions that ensure ecologic, economic, and social sustainability in relation to your holistic goal. Examples: is the problem we are dealing with a problem, or a symptom of a deeper problem? Are we dealing with the weakest link in the chain? What action will give us most progress toward our holistic goal for the least money or effort? Decisions are based on worst and best possible outcomes.

FEEDBACK LOOP When dealing with the ecosystem and its infinite complexity, assume you might be wrong and monitor according to early warning signals. Replan and adapt. Monitor to create the desired results rather than to record them. Learn from everything you do. (Learning may be defined here as changed behaviors and beliefs.)

In practice, there is one holistic decision-making model or framework for each whole under management (there are many wholes of course, and they always overlap). Instead of creating new problems, difficulties in holistic management commonly point to a need for a better or more current idea of the whole, resolution of hidden conflicts, a holistic goal that is nearer to people's actual beliefs and values, or a better understanding of the process of managing in wholes.

The three-part holistic goal is fundamental to this framework.

Holism is not an ideology, political orientation, belief or management system, or packaged solution. It is an ongoing evolution in science, knowledge, behavior, and action at all levels.

People acting holistically are true conservatives in the sense that they seek to conserve and maintain the values that are important to them. They are also pathbreakers in that they recognize that many of the beliefs and behaviors of the past and present are not sustaining these values, and are actively seeking and experimenting with new beliefs and behaviors.

We don't know the end result of this evolution, but we can guide it with our intentions and choices. The lack of effective environments for sharing learning and guiding our intentions is a major weakness. The adversarial, judgmental, and partisan approach often found in meetings, politics, news reporting, and scientific and academic discourse encourages us to resist change rather than be a part of it and guide it. The sorry result is that many of us think that meaningful participation in change is not possible.

Focus on decision-making

About 1992, Zimbabwean wildlife biologist Allan Savory hypothesized that the root cause of biodiversity loss, desertification, and declines in social, economic, and emotional conditions could be found in the underlying decision framework that people use, which tends to be linear rather than holistic. (See Holistic Management: A New Framework for Decision Making by Allan Savory and Jody Butterfield, Island Press, 1999.)

An example: many people feel certain that desertification and biodiversity loss in sub-Saharan Africa are the result of one or more of the factors on the left.

| Sub-Saharan Africa | West Texas |

|---|---|

| too many people | rural population declining |

| overstocking with livestock | stocking levels a fraction of those in 1910 |

| overcutting of trees | mesquite encroachment seen as a problem |

| drought | no bad run of droughts, except for '96 |

| cultivating steep slopes | terrain is largely flat |

| lack of education | education is high by most standards |

| poverty | abundance of money |

| lack of research and extension | abundant research and extension |

| warfare | peace |

| corrupt administration | administration uncorrupt by most standards |

| shifting agriculture | stable agriculture |

| lack of fertilizer, machinery, chemicals | plenty of fertilizer, machinery, chemicals |

| communal land tenure ("tragedy of the commons") | land is privately held |

In every single respect, the factors that appear to govern the situation in West Texas are the reverse of those in Africa. Yet severe desertification and species decline is also occurring on Texas rangeland. There is increasing conflict over resources. Rivers are silting and flooding, and small rural communities are in decline.

Many people--including a significant portion of international aid experts--remain certain that desertification is the result of overpopulation, overstocking, and so on. (See, for example, the United Nations Environment Programme's publications.) West Texas was chosen because it is flat and privately owned; otherwise many rural areas in the U.S. would suffice for comparison.

The point is not that the problems or symptoms on the left aren't grave and serious. The point is that we are in most cases managing as if the factors on the left are root causes.

What the two places have in common is that the decisions are being made in roughly the same way--according to problems and opportunities, past experience, fears and worst possible outcomes, intuition, short-term gain, research results, peer pressure, regulations, compromise, single criteria, by treating problems as goals--in short, according to "parts" rather than wholes.

This, Savory points out, is our human way of making decisions, and has probably played a role in the collapse of civilizations, and in societies that did not support cities, for thousands of years. This hypothesis is deeply challenging to those who believe that the crisis of sustainability is a modern one, and that its causes can be found in fossil-fuel technology, overpopulation, corporate globalism, or some kind of latter-day greed and ignorance.

The hypothesis also challenges those who believe that prehistoric humans refrained from damaging their ecological environment and lived in some kind of Eden. There is a growing body of evidence that prehistoric humans, using Stone Age technology, were directly or indirectly responsible for wholesale extinctions of large mammals in the Americas and Oceania, as well as for landscape-level changes in vegetation.

For most people, the effects of biodiversity loss in West Texas are partially masked by wealth. The people in West Texas, unlike those in Ethiopia and Somalia, can eat "paper"--most of them have money to buy food. The conflict is mostly being waged by lawyers rather than people with guns.

Another way of bringing the human decision-making process into focus is to look at our areas of progress and our areas of stagnation or failure.

| Mechanical | Nonmechanical |

|---|---|

| transportation | atmosphere, climate, oceans, ice |

| information processing and transfer | human relationships |

| weapons technology | resilient communities, cultures, economies |

| engineering; medical technology | participation and empowerment |

| chemical and agricultural technology | the soil resource, biodiversity |

Which side has the successes? Which side the stagnation and failure, testifying to our lack of understanding?

On the left, most of these can be considered successes only if we ignore unintended consequences such as environmental problems, social problems, and externalized costs.

In general, it has been the assumption of our society that if we manage the parts right, the whole will come right. Evidence that this is not the case is now coming from every quarter, yet our systems of knowledge and management are still structured around this assumption.

We need linear thinking. We need technology. But our overall management needs to become holistic.

Ranchers, farmers, some illiterate African villagers, numerous individuals and families, and several nonprofit organizations are managing according to a single but comprehensive holistic goal that includes their quality of life values, forms of production to sustain that quality of life, and future resource base needed to sustain those forms of production. Ecosystem sustainability is not an add-on criterion to this kind of decision making--it is built in. Sustainability is not the result of which tools you use--an enormous amount of desertification and soil erosion over the last 10,000 years has resulted from very low-tech tools used by well-intentioned humans. Sustainability results from the kind of decision making you use.

Many people are asking, what is sustainability? How can we measure, define, or encourage it?

But there are also people who are asking a fundamentally different question. They see the S word as a verb and ask instead, what do we want to sustain? This is a hard question for most of us, but the ongoing work of answering it is the foundation or starting point of holistic decision making.

Not only is SUSTAIN a verb, but it is a verb that requires both a subject and an object. For example:

Love sustains marriage.

Listening sustains trust.

Agriculture sustains civilization.

The United States Department of Agriculture, price supports, and the land-grant university system sustain American agriculture.

But wait a minute. Is this last one the truth, or does it reflect a hope, and a forlorn one at that? Isn't it the soil, and the values, experience, and habits of our land stewards, and markets that in turn sustain these--aren't these what sustain American agriculture? In the midst of fundamental social, economic, and environmental change, we may need to reassess what sustains what, and not take past answers for granted.

If you ask any group of people anywhere in the world, "How many of you woke up this morning with the intention of destroying the world?" nobody would raise their hand. So if we're doing it without intention and yet we're doing it anyway, it means that it's imbedded in how we do things as opposed to being something that we want to do. And that tells me it can be reversed.Paul Hawken, author of The Ecology of Commerce

It is important to distinguish between decision-making processes and administrative restructuring. Frequently we believe that we change our decision-making framework when local decisions become national ones, or vice versa, or when decisions are made by a different group of people than previously (as when the U.S. Congress shifts from one party to the other, or when we replace an elected official with "bad" priorities with one with "good" priorities). In the majority of cases the linear or standard decision making continues.

We spend a great deal of energy trying to shift ideology, priorities, or people's position on particular issues, without regard for the fundamental and underlying decision process itself.

Holism: A different paradigm

In 1924 Jan Christiaan Smuts retired from the South African Prime Minister's job after his party lost the election. During the next two years Smuts wrote Holism and Evolution, a deeply felt response to the ideas of Charles Darwin, the new physics of relativity and quantum mechanics, and his own experiences.

A soldier, statesman, and amateur naturalist and botanist, Smuts's strategic efforts against the British in the Boer War were the admiration of many. Winston Churchill was once his prisoner, as was Gandhi. Later, Smuts was active in the League of Nations.

In 1927 Smuts lectured at the University of Witwatersrand.

The world consists of a rising series of wholes. You start with matter, which is the simplest of wholes. You then rise to plants and animals, to mind, to human beings, to personality and the spiritual world. This progression of wholes, rising tier upon tier, makes up the structure of the universe. . . .We find, instead of the hostility which is felt in life, that this is a friendly universe. We are all interrelated. The one helps the other. It is an idea that gives strength and peace and is bound to give a more wholesome view of life and nature than we have had so far.

Wholeness is the key to thought, and when we take that view we shall be able to read much more of the riddle of the universe.

In his book, Smuts coined the word holism in English. For him the word referred to a fundamental tendency or organizational principle. He felt that evolution operated in a holistic fashion, and was neither the sum of numerous and unrelated changes, nor the outcome of a grand preconceived design. In Holism and Evolution, Smuts anticipated a fair amount of modern chaos and complexity theory.

For Smuts, creative evolution was the central fact, and even Darwin's successors and proponents did not take sufficient account of it. Smuts deplored the ongoing debate between those who believed in a mechanical evolution, and those who saw Spiritualism as the beginning and end. Yet 75 years later, this debate continues. The Gaia hypothesis advanced by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis has been roundly criticized as "teleological" (with some kind of preordained result) by those who have no appreciation for the qualities inherent in self-organizing networks or structures, whether living or nonliving. (See Fritjof Capra's The Web of Life or James Gleick's Chaos for some more detail on self-organizing networks.) Again, Smuts:

Science and philosophy alike are vast structures, laboriously built up on the basis of certain fundamental concepts. The attempt I am making is to introduce into these elaborate systems a new basic concept, perhaps more fundamental than any of them. And it will be clear that such an attempt must be a most difficult and hazardous one; it involves far-reaching readjustments of settled points of view, the reopening of questions long looked upon as answered and done with, the envisaging of many old problems from a new and novel point of view. To insert the spear-point of the new concept into these vast closed settled systems may at first sight appear a revolutionary, an iconoclastic procedure. But I hope I shall be able to show that this is not really so, that at any rate to begin with the concept of Holism will fit constructively into the work of the past, whatever its ultimate effects may be in the reshaping of these systems on the new basis; that in relation to the old concepts it appears in the field not as an enemy but as a friend and ally in the great battle of knowledge, and that it will help materially in the solution of problems which are practically insoluble on the lines of old concepts. The concept of Holism is brought forward as a reinforcement at a critical point in the battle, in the hope that it will help to bring victory. But I do not conceal the further hope that in its ulterior effects it will lead to a recasting of much of the situation of knowledge as at present envisaged, and will render obsolete and replace much that is at present considered valuable if not fundamental both in science and philosophy.

Later in his life Smuts wrote:

I am content to be patient and wait for actual results. New ideas take a long time to filter into the public mind, and Holism may not produce early results, but in the long run and in the end I have little doubt that it will secure its place in the development of human thought, and will help lead public opinion away from the destructive atmosphere of the past to that saner and larger viewpoint, which will once more bridge the gaps and fill the fissures which the mechanistic science and philosophy have created for the human spirit.

Complex world of interconnecting parts

Overlapping wholes

How many different types of relationships are there in the picture of interconnected parts?

How does the treatment of white space differ?

How many different types of relationships are there in the overlapping wholes?

Which view would lead to an overriding belief in competition, in scarcity?

How might the notions of causation differ?

Wholes have properties that their "parts" do not have. If you had a roomful of people, half of whom knew everything there was to know about hydrogen and not much else, and the other half knew all there was to know about oxygen, and you showed them water, they would not recognize it. Water is not a compromise between hydrogen and oxygen. Water is not a middle ground. Water is something different.

It is sometimes remarked that the western scientific world view starts in the middle--for example, technological processes--without sufficient regard or respect for the fundamental basis of the universe--matter, space, time, water, algae, ants, phytoplankton, ecological relationships--and also without regard for ultimate ends or goals.

Morris Berman, in his 1981 book The Reenchantment of the World, contrasts the conventional scientific view with the holistic view of Gregory Bateson as follows:

| Conventional scientific view | Batesonian holism |

|---|---|

| no relation between fact and value | fact and value inseparable |

| nature is known from the outside, phenomena observed out of context | nature is revealed in our relations with it, and phenomena can be known only in context (participant observation) |

| goal is conscious, empirical control over nature | unconscious mind is primary; goal is wisdom, beauty, grace |

| descriptions are abstract, mathematical; only that which can be measured is real | descriptions are a mixture of the abstract and concrete; quality takes precedence over quantity |

| mind is separate from body, subject from object | mind/body, subject/object, are each two aspects of the same process |

| logic is either/or; emotions are epiphenomenal | logic is both/and (dialectical); the heart has precise algorithms |

| Atomism: | Holism: |

| 1. only matter and motion are real | 1. process, form, and relationship are primary |

| 2. the whole is nothing more than the sum of its parts | 2. wholes have properties that parts do not have |

| 3. living systems are in principle reducible to inorganic matter; nature is ultimately dead | 3. living systems are Minds, are not reducible to their components; nature is alive |

Often we do not recognize the power of paradigms. When someone who does not share our assumptions or paradigms does not see something that we think is obvious, we often become angry. We think the person is blind, dishonest, corrupt, immoral, stupid, or close-minded.

The psychology of change

Few people begin to use a holistic decision making framework merely from being exposed to the concepts or understanding the rationale for change. This reflects our human way of change. Often, rationality or demonstrated benefits have very little to do with whether or not change happens.

Scientists studying complexity and "chaos" are realizing the inadequacies of conventional paradigms or assumptions about reality. But, as is so frequent in human affairs, there is backlash against the new concepts, and struggles over authority and power. (See Gleick's Chaos and Waldrop's Complexity, relisted at the end of this document.)

You are not required to accept the perspective of holism as established, proven, certified, researched, commissioned, or even widely accepted fact. It is not an acknowledged majority viewpoint. However, I encourage you to adopt holism as a working hypothesis if you have not already done so, and to work with these concepts on that basis. In other words, what if the universe functions in wholes? How would you live your life, make your day-to-day decisions? After a while, what sort of results do you think you are getting?

Three choices for progress:

- Do nothing.

- Do more of the same but do it harder.

- Do something different.

Which is the most popular choice?

Five steps to adopting a new idea:

- Ridicule it.

- Criticize it.

- Ignore it.

- Copy it.

- Claim it as your own (and call it something else).

Vicki Robin, author of Your Money or Your Life, commented that there are three choices for change.

- We can try to carry the vision to everyone, without sacrificing one iota of its integrity.

- We can slice and dice and soundbite the vision, try to adapt the message to people's level of understanding.

- We can try to craft technology and regulation so that people can continue to live unexamined lives without harming others or the ecosystem.

Bob Chadwick's human change model

The results we are getting are outside the circles. If you want to modify the results that an organization or a person is getting, you deal with the two outer layers--strategies and actions. If you want to transform the kind of results you are getting, you must go down to the level of behaviors and beliefs. Stephen Covey calls this "inside-out" change.

Often we focus only on getting people to act differently. We nag. We pass legislation that penalizes certain activities, or rewards others. Sometimes we encourage people to adopt management strategies or systems, or political strategies.

We cannot achieve long-lasting change unless we deal with the resisting forces--which are often at the deeper level of behaviors and beliefs. Many of our purposes require change or motion at the level of behaviors and beliefs, yet the solutions we propose deal typically with strategies and actions--in other words, with symptoms. Most of our meetings deal with agendas, strategies, actions, projects, proposals, and we are often afraid of encountering conflict or resistance to "touchy-feely" stuff. (For an excellent practical introduction to a different meeting process, see Chadwick's Beyond Conflict to Consensus.)

Behaviors in the above model refer to our deep-seated habits--such as listening to others with respect, being reactive rather than proactive, or other habits that we frequently do not acknowledge.

How would you characterize U.S. farm programs in light of the model above?

How would you characterize our society's efforts to deal with environmental deterioration? Are they modificational change, or transformational change?

TASK: Classify the following statements as actions, strategies, behaviors, or beliefs.

The speed with which an organization moves is more important than the direction.

What is visionary, and what is practical, are two different things.

In order for a strategy to succeed, it must be complicated and expensive.

That person's ideas or feelings are unimportant.

There should be no grazing in Hells Canyon.

We need to cut more timber in Hells Canyon.

People's values are different.

People are untrustworthy.

There is nothing I can do about the situation.

We must try a little harder.

People must have their basic needs met before they can think about higher things.

Resources are scarce, and I must struggle to get my share.

You can't please everyone.

Another way to look at the levels of change was suggested by anthropologist Edward Hall in his book The Silent Language, published in 1959. Hall suggests that culture and change operate on at least three levels:

- the technical, which we learn by instruction, logic, and analysis;

- the informal, which is seldom described, and which we learn by imitation (for example, meeting styles and decision processes);

- the formal, very seldom described or explained, which we learn by precept and admonition (dos and don'ts--for example, don't challenge accredited experts without proper credentials).

Formal or informal systems cannot easily be changed by technical approaches alone.

If a person really wants to introduce culture change he should find out what is happening on the informal level and pinpoint which informal adaptations seem to be the most successful in daily operations. Bring these to the level of awareness.

Edward T. Hall, The Silent Language The "informal adaptations" are what ManagingWholes.com seeks to bring to awareness.

Changing our perceptions

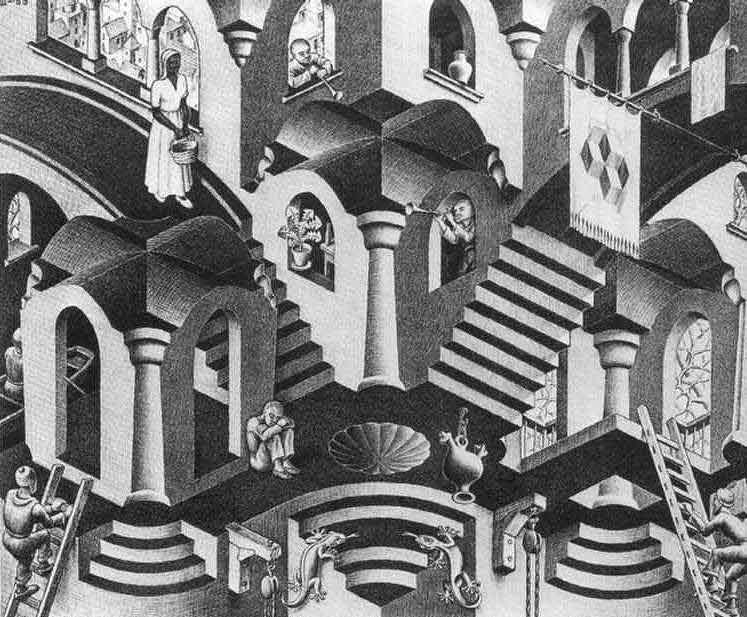

Here is a reproduction of Dutch artist M. C. Escher's 1950s lithographic print Convex and Concave.

Cover the right half of the picture with a piece of paper. The cues--the woman carrying the basket, in fact everything in the picture but the architecture itself--lead you to see the architecture and the perspective one way. These are cues.

Now try covering the left half of the picture. The cues lead our perceptions to a different perspective.

People vary in their ability to shift perspective at will. How far can you "participate in" or extend the perspective that is cued by the figures on the left into the right side of the picture, or vice versa? How far can you imagine the woman with the basket walking down the stairs and then up the stairs on the other side?

Shifting our perspectives, like shifting our paradigms, is largely a matter of cues. Our responsibility for self-education requires that we become aware of the cues that we respond to. These may include childhood scripting, our education, training, and upbringing, and much of what we regard as our habits. In conversation, in meetings, in making our daily or yearly plans, and in all of our decisions, we are responding to cues.

Escher's picture shows that although we are powerfully affected by cues, we do have choices. We can see the picture as either convex or concave, or both.

As Stephen Covey says, a constant of the human situation is our ability, our human freedom, to choose our response to a stimulus. By recognizing the cues that influence our perceptions, we enable ourselves to change them. In addition to self-awareness, we need the other human capacities--conscience, independent will, and creative imagination--to effect lasting change.

He who cannot change his mind, cannot change anything.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Guidelines for leading paradigm shifts

- Introduce anomalies and help people perceive them.

- Provide a clearly defined new paradigm.

- Build faith in the new paradigm.

- Help people let go of their old paradigm.

- Give people time in the neutral zone.

- Give people touchstones (ways to tell what is genuine).

- Provide a safety net.

From Banishing Bureaucracy: The Five Strategies for Reinventing Government, by David Osborne and Peter Plastrik (Addison Wesley 1996).

Best efforts and hard work, not guided by new knowledge, only dig deeper the pit we are in. The aim of this book is to provide new knowledge.

Knowledge necessary for improvement comes from outside. . . . There is no substitute for knowledge.

The first step is transformation of the individual. This transformation is discontinuous. It comes from understanding the system of profound knowledge. The individual, transformed, will perceive new meaning to his life, to events, to numbers, to interactions between people. The individual, once transformed, will:

Set an example.

Be a good listener.

Continually teach other people.

Help people pull away from their current practice and beliefs and move into the new philosophy without a feeling of guilt about the past.

from W. Edwards Deming, The New Economics

Holistic decision making or holistic management--action based on knowledge of wholes--is an ongoing evolution. The present moment, the present state of affairs, is not the endpoint of that evolution.

As Bob Chadwick observes, holistic management, consensus building, and other processes are not ends or purposes in themselves. They are how-tos, or tools. The need and desire for real results, rather than allegiance to particular methods, is what is most important.

When people want results that are significantly different--socially, economically, and ecologically--they are faced with transformational or paradigm change.

When I reflect on what I've learned from the people I've visited in the course of publishing Patterns of Choice, there seem to be three common (and certainly overlapping) threads.

1. Holism, the simple but far-reaching idea that wholes are greater than the sum of their "parts." This is also the principle of systems thinking, of synergy, win/win, and abundance. Instead of just dealing with issues or problems, they concentrate on enhancing systems. Creativity and monitoring are essential.

2. Working from the asset base. Many people I've met aren't just taking aim at problems, faults, labels or diagnoses, and deficiencies. They're working to build capacity in people, in soils, in communities. Along with this comes the need to work from a holistic goal, life purpose, or best possible outcome.

Asset-based development is not centered on strategies or programs, but on people and the ecosystem. It is responsive rather than strategic, and it is about empowerment rather than control. It requires a belief in the capacities of people and of nature. It works toward best outcomes, rather than being based on worst outcomes.

A different style of leadership goes along with this. As Bob Chadwick says, "Servant leadership is where we're headed. Not a leader who tells you what to do, but a leader who brings diverse elements together and lets them figure out what to do."

3. A different attitude toward time. Time is an investment, an opportunity, rather than a cost or expense. When people work toward creating opportunities rather than meet deadlines, it becomes easier to see underlying problems rather than surface symptoms. They are "going slow to go fast," working toward improvement rather than perfection, managing process rather than events.

Merve Wilkinson is a good example. He has "a long-term perspective and a day-to-day participation in a living landscape that evolves over decades and even centuries." Or, as Wallowa County forester Bob Jackson puts it, you manage a woodlot and create results "one day at a time."

For examples of how this kind of decision making plays out in practice, in specific situations, see any of our topic headings.

The importance of the immediate environment

In the matter of paradigm change, the immediate environment and the cues it supplies are critical. If you live or work in a place where urgency, criticism, and linear thinking are expected and rewarded, it will be difficult for you to think or act differently, or to convince anyone else to do so. That is why no amount of theory or abstract knowledge can create paradigm shifts. It takes skill and practice at creating a different psychological environment--see Bob Chadwick's consensus building advice for creating an interpersonal environment that supplies different cues, where transformational change becomes possible.

Further reading

These are useful for "getting out from under" what you may have been taught about how the physical and biological worlds operate, as well as human thought and organization: Savory, Allan, with Jody Butterfield. Holistic Management: A New Framework for Decision Making. Island Press, 1999. (The previous edition was titled Holistic Resource Management, Island Press, 1988.)

Smuts, Jan Christiaan. Holism and Evolution. Reprint, Gestalt Journal Press, 1986.

Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. This book was one of the first to examine the "paradigm effect"--the way existing beliefs prevent acceptance of new beliefs.

Hall, Edward T. The Silent Language. Doubleday, 1959. An anthropologist's still-startling description of the less acknowledged aspects and levels of culture and communication, and the near-impossibility of fostering change without recognizing these aspects and levels.

Berman, Morris. The Reenchantment of the World. Cornell University Press, 1981.

Capra, Fritjof. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. Anchor Books, 1996.

Chadwick, Bob. Beyond Conflict to Consensus: An Introductory Learning Manual.

Covey, Stephen. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. Simon and Schuster, 1989. Also highly recommended are his First Things First and Principle-Centered Leadership.

Gleick, James. Chaos: Making a New Science. Viking, 1987.

Waldrop, M. Mitchell. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. Simon and Schuster, 1993.

Wheatley, Margaret. Leadership and the New Science. Berrett-Koehler, 1992.