by Dennis Wobeser

In 1999, Dennis and Jean Wobeser, of Hi-Gain Ranching, in Lloydminster, Alberta, won the Emerald Award in the small-business category. This is the major Canadian environmental award, and this is the first time it has been won by an agricultural operation. In the words of the press release that accompanied the award:

Dennis and Jean Wobeser have been in the cattle business since 1963. For over 20 years they ran a custom feeding and feedlot company that, at its peak, handled 7,000 head of cattle. In the late 1980s, the Wobesers, along with daughter Kelly, son Brady, and four employees, decided to transform their high-technical/high-input commercial feeding operation to a low-input, nature-based grazing operation. Hi-Gain Ranching now manages 4,500 acres with most of that land dedicated to seeded pasture and maintenance of natural areas, supporting 600 cows and 600 to 800 yearlings. The Wobesers' approach has resulted in healthier and higher-volume grass, increased organic matter in the soil, more diversity in plant species, and an increase in beneficial insect species. Bare ground has been decreased and healthier land has been increased due to disallowing pesticides and chemicals. The effects of floods and drought have been reduced due to a layer of thatch (dead and decaying plants) on the surface of the ground, which increases the water holding capacity of the soil and reduces erosion and runoff. Hi-Gain Ranching is truly a demonstration of a healthy and vibrant ecosystem.

The following is from a too-brief interview with Dennis Wobeser. Thanks much to Arnold Mattson and Brady Wobeser for their comments and contributions.

Dennis: I graduated from university in 1961. There's never been a faster explosion in technology in agriculture than there was in the twenty years after 1960. Now we're finding out that not only do you go broke buying things to help you, but you've destroyed the soil, the base. That's the turnaround.

All my life I've wanted to be a cattleman. When I got into Holistic Management I realized that collecting solar energy through growth on the land was more important than the animals, and the animals were only tools. Begrudgingly I had to drop my sacred cows from number 1 to number 2, and put growth ahead of it. We've got friends just south of us, Larry and Toby Bell, and they started to convince us that we weren't looking deep enough yet. They convinced us that all our future and everything is dependent on the health of our soil. If you have healthy land, you'll have healthy plants, which you can then harvest by livestock if that's the way you choose. Now the cows are the third priority: put the soil first, then the growth, then the animals.

It's interesting to see the world accepting this change, this new idea. That's what ladies like Sally Fallon [author of Nourishing Traditions: The Cookbook that Challenges Politically Correct Nutrition and the Diet Dictocrats] are talking about. The fact that butter was bad, that beef was bad, that fat was bad, all of that has changed. We're back to healthy diets again.

HRM [Holistic Resource Management] used to have an annual meeting in Albuquerque. For about five or six years, we went to it. They'd have a choice of short courses. After about five or six years, Jean and I are sitting in Albuquerque taking the goal planning course--we found ourselves full circle. We started to realize quality of life. That might have something to do with my age.

People said, what did you learn from Holistic Management? I said, I finally learned that there is a light at the end of the tunnel, and no, it isn't just another freight train. That's when the quality of life thing started to come.

Allan Nation keeps saying, when you're fifty, you're running out of steam, so you have to use your expertise and the young people's energy to put it together. Ernesto Sirolli said that the three things that were key were production, finance, and marketing. We're very fortunate here, Brady he's got the energy and can do the production, Kelly's just really good and likes the financial planning stuff, and I can still stumble around and go to a market or two and do the marketing, so we've got a pretty good team.

The key to the whole thing is the people aspect. If you can just get the people thinking right, there's no stopping you. There's so much potential out here right now.

The Devon management club is a support group for holistic managers. Meetings are monthly, include a potluck supper, and the host has to come up with a worthwhile topic.

Dennis: In our club we're weak on the people, goal aspect. Particularly the men, they're so prone to jump out and go recreational fencing or farming--it's the hardest by far to get people into the people aspect.

Once you get involved in this aspect, it flows. For our management club, the biggest thing has been the involvement of the entire family. To get more involvement by everyone has been key.

Everything does cycle. What was working for a while is not necessarily right forever. Somebody said, where would you have been if you'd been involved with Holistic Management twenty years ago? Twenty years ago I was too smart to listen. Because it wasn't really right for the times.

Like the feedlot--it was right for the times, but then we had to realize that we had to do something totally different, or get a lot bigger. When we looked at the financial aspect of the inefficiencies of growing and feeding grain to confinement livestock, we didn't like it. Now we're exceptionally glad we made the change. Now everybody's yowling about the price of diesel fuel and gas, and we don't need very much around here, and that helps a lot.

Working with nature instead of against nature looked exciting. And the economics--we were going through vast amounts of money here and hanging on to very little of it.

Neither Kelly nor Brady wanted to carry on with the feedlot. And it was a rat race.

Brady Wobeser: The grass management beats slogging around the mud in the feedlot by a long ways. With the feedlot, we didn't have time to do anything.

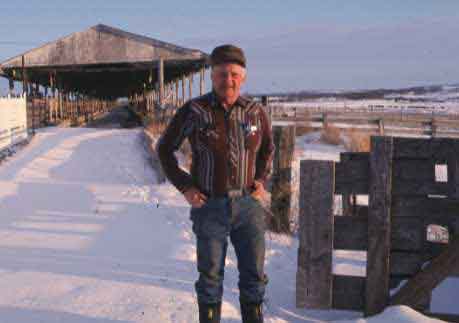

Dennis Wobeser in the central alley of what was once a 7,000-head feedlot.

Dennis: Everything--labor, money, effort, land--everything was geared to supporting this feedlot. It devoured everything. We said, there's something wrong here. Let's get back to managing the land. If there's some aspect to the feedlot where it can fit into that, we would still do it. Otherwise, no, we won't do it.

We wanted to move the feedlot outdoors. We wanted the cattle to work to find their feed, and we wanted them to spread the nutrients back on the land in the form of manure.

We've always bought a lot of the feed. The biggest breakthrough was when we found out a cow can lick snow instead of having to have water. That allowed us to move the herds away from home, to where they're doing some good on the land.

Brady: 95 percent of the reason you see all these cows right around the yard all winter is that they won't let them away from that water.

Dennis: Allan Nation said it's fairly simple: plants want to stand still and animals want to move. Why don't you let them? But a cow is just like any person or anything. You put them on welfare, they get to liking it. But they don't need it. More and more we just marvel at how adaptable these cattle are. Things that people said you couldn't do. To hell you can. You can do it.

We grew up with the European philosophy, that all the cows were tied in the barn. I often wondered why that was. That's the way my dad was, you tied everything up in the barn.

We have a lot of opportunity here, and we're just starting to scratch the surface. If the consumer keeps demanding more healthy food, then we're really on the right track. But we'll always have cycles and so forth. We've got to try and not pattern our operations after price, we've got to pattern them after cost. Do the best you can with what you have, where you are. We keep uncovering more adaptability and flexibility in these cattle.

The profit margins per animal made it look to us like it didn't make a lot of sense to finish cattle anymore. So we went to backgrounding.

Now, on the prairies here, the tremendous attempt by farmers to diversify their operations, to diversify their market, and still keep on being a grain farmer, has led them into backgrounding--selling the crop through calves. We've got so many people who say, if I had more pasture I'd have more cows. But they've got ten quarters of farmland behind the house, and they absolutely will not consider putting it into grass. But they will consider harvesting it as a forage as silage, and build a confinement situation to feed it to calves. Because of that, they're bidding all or more than all of the margins out of backgrounding. They are far less market-disciplined than the big feedyard is.

So it's hard to be in the backgrounding business. The opportunity is in supplying them what they want--that's a calf that's eligible to go to backgrounding.

We're a long ways away from the grass-fed thing in North America because we still have political manipulation trying to encourage the production of grain. As long as we have that, we'll have cheap grain that we have to dispose of through livestock. The bottom line is still coming back to: the cheap production is on grass. And the other thing that's brought us in this area to the cow, is that we've now realized that the cow can survive strictly on byproduct during the winter feeding period. Our cows are wintering on bales of straw, with the chaff put back in the straw, and supplemented with a pea/lentil screening pellet. We've got some neighbors growing milling oats. The oats have to be hulled. The oat hull, ground up, is producing an extremely good cow feed. We're got a lot of cows in this district--by and large people who are involved in Holistic Management--that cows are existing 100 percent through the winter on byproduct feed--the amazing ability of the ruminant animal to adapt to those situations!

Blake Holtman used to say, my land was trying to tell me something, and I wasn't listening. How true that is!

We've more than doubled our production.

Brady: We've doubled it since 1996.

Dennis: The soil has started to come alive again.

What we just finished doing with the feedlot wasn't necessarily wrong. It might have been right at the time. But the whole key is, the most difficult thing for society to accept is change. We have to learn to accept change. Nature cycles, everything is trying to do that to us. And we get in real trouble if we start to ignore that, cycles and change.

Most of the Holistic Management spread is happening by osmosis.

Arnold Mattson: Dennis is being modest. He says it spreads by osmosis but he coaches and mentors a lot of people.

Dennis: I've enjoyed that part of it. The feedlot started that. It was a custom lot, it was a people place, so we learned to work with people. We've enjoyed helping people.

Brady: When we quit custom feeding it was like a ghost town around here, because people weren't coming in. Now it's just about as many people coming in--related to renting grass, etc. Our neighbors don't think we're crazy anymore.

Dennis: Jack Lessinger has a saying, you do not change the people's minds. You change the people. [Lessinger is the author of Penturbia; see www.lessinger.com.] That's where we're leading to next in western Canada.

This area that we're moving into [the Wobesers recently purchased some land in Saskatchewan]--many guys my age. The kids are gone, and they are not coming back.

Sometime since the 1930s, as a society, we've lost sight of quality of life, and replaced it with standard of living, as far as goals are concerned.

In the Stockman Grass Farmer of January 2000, James Landis makes five predictions ("One grass farmer's vision of the future"):

- I predict real prices of farm products will trend lower throughout the next century. Allow for spikes and dips, allow for inflation (we're talking real value).

- Technology will never find a more efficient way to convert the energy of the sun into human food.

- The environmental movement's power will decline in the next century.

- U.S. graziers will be able to compete with overseas farmers and even excel at efficient milk and meat production throughout the next century.

- I predict the breakdown of the welfare system and the shift of the United States into regional economic units.

I think all five of those have a lot of merit. There's no point in sitting back and yowling about your situation. All you have to do is recognize your situation and operate accordingly. It can be great.